This article contains words that readers might find offensive. This includes swear words and offensive words relating to sex and race which are, in most instances, direct quotes from original documents. The inclusion of these words is designed to show the attitudes of the day and to be historically accurate and in no way does it reflect the authors own views.

It is the early hours of a Friday morning in July 1923. Two men and two women are leaving ‘The Palm Club’ in Gerrard St, Soho. Saturated with drink, both men vomit on the pavement as one of the women shouts

“Don’t fetch your bloody guts up you boys!”

Swaying and loitering, the group argue noisily about getting a taxi. The footman looks on anxiously, praying for their speedy departure. Customers leaving drunkenly at this hour of the morning draws too much attention and you never know who is watching. The footman eventually gets them into a cab but with great difficulty. His efforts are in vain however, as not far away, Sergeant Goddard and Police Constable Wilkin are keeping external observation on the comings and goings at the Palm Club.

Sergeant Goddard and Police Constable Wilkin

By 1923, Sergeant Goddard had been stationed at ‘C’ Division, Vine Street for a decade. He had been given the responsibility for supervising nightclubs since 1918 and with his protégé, Police Constable Wilkin, they covered the vice district of Soho. Being instantly recognisable, they were prevented from carrying out undercover operations, keeping external observations instead. But as they counted the ‘prostitutes’ entering and leaving the Palm Club, the two were far from squeaky clean themselves. It would be another six years before their names were embroiled in a national scandal, alongside the very club proprietors that they sought to prosecute. For the time being however, their stars were ascending and they were frequently commended for their work.

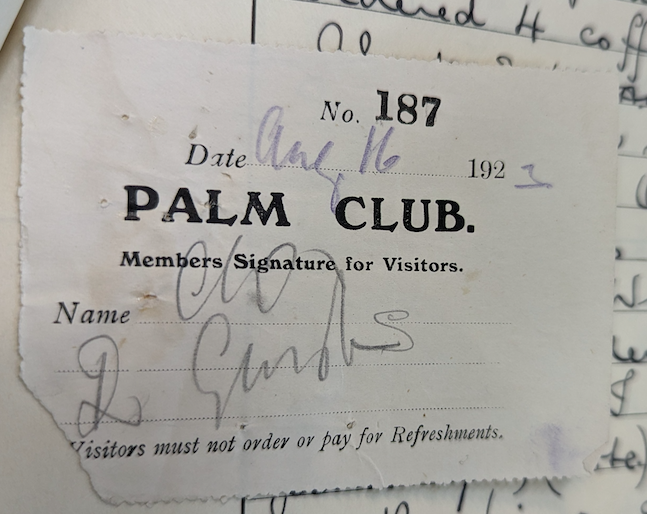

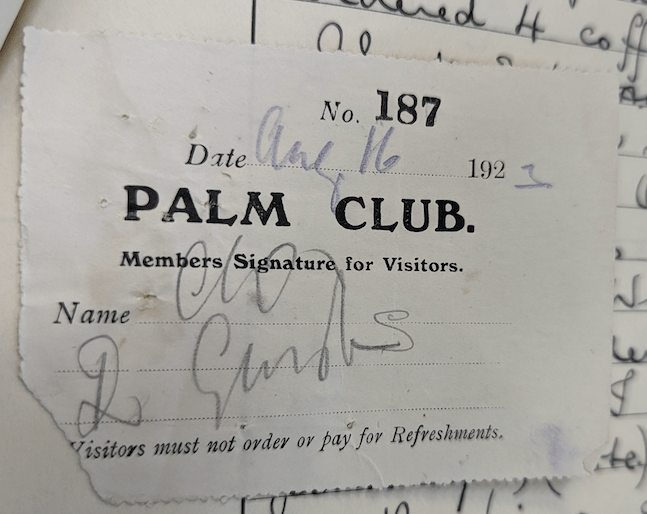

In the 1920’s, clubs had to be registered at the local police station where they were required to set out their purpose and the hours they planned to keep. They could stay open all night if they wished, but alcohol was not to be served after 11pm. The Palm Club had been registered at Bow Street on May 30th of that year and as such it had only been operating for a couple of months. Gerrard Street had a reputation for seedy clubs, sex workers and men of questionable character and it is quite probable that the club was on Goddard’s radar as soon as it was registered.

‘The Palm Club’ (No. 6) sat opposite Mrs. Meyrick’s ‘43 Club’ (No. 43) and the two premises had an interesting relationship. In 1922 the ‘43 Club’ was itself the subject of police observation. It was noted that tickets for the ‘43’ had to be purchased from number 6 across the road. It is unclear as to whether there was any connection thereafter.

As Sgt Goddard and PC Wilkin kept watch over The Palm Club on that July evening, Goddard counted at least twelve ‘prostitutes’ leaving the premises between 11.30pm and 3am. To varying degrees, everybody, it seemed, was under the influence of drink. Men urinated or vomited on footways and a woman was seen pulling her skirt up to her waist and gesticulating at her groin shouting “I’m clean enough for a fucking prince!”

Goddard and Wilkin returned to keep observation on a further four dates in the month of July, noting that those leaving the club included a helplessly drunk man lying in the gutter, customers singing and dancing drunkenly in the streets, a man falling and bloodying his nose, women urinating on footways and shouting obscene language and men removing their jackets and commencing to fight. As a result of these observations, it was decided that officers should enter the club undercover.

The challenge with such operations was finding the right people. Potential recruits needed to be trustworthy but convincing enough to fit in. Once a raid was completed and the officers were ‘unmasked’ they were no longer useful; a constant supply of unknown faces were required. As a result, the undercover jobs often fell to the newest and youngest recruits.

Jack Mepham was twenty-five when he entered The Palm Club for the first time. His family originated from Burwash in Sussex and his father worked on the railways. Jack had served in the First World War, and on signing up he had described himself as an electrician but by the 1921 census he was living in police quarters at 82 Charing Cross Road. His co-worker on the job was Harry Steggles Davidson. He was born out of wedlock in Norfolk but his father went on to marry his mother at a later date. This information was gleaned from his enlistment record when he joined the Royal Navy at just 12 years old. At the 1921 census Harry was in training to be a police officer and living at Peel House, a Metropolitan Police Training Academy in Pimlico. Davidson may well have been spotted by Inspector Abiss, who lived on site with his family at Peel House and who would preside over the raid at the Palm Club. Davidson and Mepham would have been exactly the kind of fresh-faced officers required for an undercover sting.

The Police Go Undercover

After receiving instructions from Sgt Goddard, Davidson and Mepham entered the club at 11.30pm on August 8th. A uniformed footman stood at the door and in the hallway, a man in a dress suit issued tickets; no questions asked.

Mepham described the dancehall “a long room with four or five tables at the corners. The orchestra consists of two men playing piano and jazz drums.” On entry, only two women are dancing but soon Mepham and Davidson are dancing with them and the officers are told that drink is available upstairs.

Despite the warning on the ticket that only ‘members’ can purchase drinks and despite the hour, Mepham and Davidson are able to obtain drinks with ease. They purchase two lemonades, one port and one whisky and soda. They note a ‘Chinaman’ sitting alone at a table.

Returning to the dancefloor, the swell of the crowd is noticeable and dancing is in progress. Mepham’s report states that ‘girls solicited’ and two left with men. By the time observation ends at around 2am they have purchased: seven whisky and sodas, two lemonades, one port and two large packets of cigarettes.

Under the instruction of Inspector Abiss, Davidson and Mepham carry out a further six undercover visits during the month of August. Each visit follows a broadly similar pattern. The gentlemen enter without question, paying 5 shillings apiece and are soon joined by single women. Their companions remain with them while they are in the club, the officers dance with them, supplying them with whisky, cigarettes and sometimes sandwiches and coffee. On each occasion the ‘Chinaman’ is present.

One Friday night, Davidson’s female ‘companion’ is very drunk and begins quarrelling with Mepham’s companion. Despite being warned by the management, she refuses to let it go and Davidson and Mepham feel obliged to remove her from the premises, taking her home in a taxi to Hunter St. When they return to the club the following evening, the manager asks them “How did you get on with those girls last night?”. On this visit things seem a little quieter, they buy the manager a drink and he apologises that there “were not more girls in tonight.”

A few days later the evening is far more energetic. Davidson and Mepham arrive at around 12.40am. They note two very inebriated women ordering brandies and a drunk man at the piano. The piano player is accompanied by a woman lifting her clothes to her waist and who, in Davidson’s words, “did a lot of high kicking.”

As usual, the officers are soon joined by two girls and four whiskies are ordered. A drunk lady asks to join the party saying “My companion is blotto, let me come and talk to you.” The companion in question has collapsed drunkenly in the corner but the disinterested woman says, “let the old cow lay, buy us a drink boys.”

The manager sings a song and while Davidson and his companion go upstairs to get a drink, Mepham’s lady says “Come on let’s go and have a bloody dance” afterwards asking “how about coming home with me after we have finished here?”. There is no record of Mepham’s response.

Clearly entering into the spirit on this evening, between them Davidson and Mepham order twenty four whisky and sodas. Perhaps the fact that Mepham had just turned twenty-six might have meant he was in a celebratory mood?

The way in which some police officers seemed to acclimatise to club life did not go unnoticed by their superiors. Particularly on the issue of expenses, correspondence exists showing concerns about the carefree way in which some officers spent money in the clubs. By the time the entrance fee, cloakroom fee, drinks, food, tips and taxis were accounted for, undercover work was an expensive business.

More interestingly, further documentation exists to show that despite the resources that went into monitoring and closing down such establishments, at the end of the year, the net number of clubs operating was broadly similar, or in some cases had actually increased. We might wonder if there was a desire on the part of the lower ranking officers to keep the merry-go-round turning? For so long as the clubs and police were locked into the war, the ordinary bobby had a jolly good time and in some cases even financially profited from it.

The Gangs

Notwithstanding its significant perks, police work in Soho was undoubtedly dangerous. The following evening Davidson and Mepham are back at the club, although Davidson enters some time before his colleague. A woman remarks “An awful rough crowd in tonight, they are pulling out revolvers.” Davidson proceeds upstairs where he sees seven men at the bar “clamouring for drinks”. They are served with whiskies but when they ask for more the manager says “We have sold right out”. The gang comes to the piano, singing choruses and shouting “Any bookmakers here?” and demanding “What about another fucking drink?”. In an attempt to remove the gang the bar is shut and the band stops playing. The manager apologises to Davidson saying that once he gets rid of the crowd things will return to normal. “They have come and gone three or four times now, I don’t suppose you know them, it is the Sabini gang, but the head one is not here tonight.”

Gangs were a perpetual problem for nightclubs in Soho. In her memoirs, Mrs Meyrick describes how they would arrive in large groups, well dressed and politely refuse to pay for their drinks. Calling the police was a gamble. It attracted unwanted attention and the gangs could get nasty. With the heady mix of testosterone, drink and guns, it was not unusual for shots to be fired inside clubs. The only way to get rid of the gangs was to freeze them out by claiming that the bar was dry, or more often than not, to come to some kind of agreement with them.

While Davidson waits for things to return to normal, Mepham struggles to enter the club. Fighting has broken out on the footway and the club door is closed in an attempt to keep the Sabinis out. Mepham finally gains access and as usual he is soon joined by a woman. He notices the ‘Chinaman’ enter the hall.

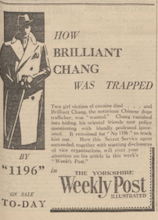

“Do you remember the Freda Kempton case?” says the woman. “He is Chang but I think that job broke him. He runs this place.”

Freda Kempton and Brilliant Chang

Brilliant Chang was a charismatic Chinese businessman; attractive, well-dressed and well educated. He liked women and he liked cocaine, as did many Soho men at that time. However, he came to the attention of the press after the death of Freda Kempton, helping to crystallise the moral panic of ‘Yellow Peril’. Although Chang’s behaviour was predatory, as shown by the identical pre-written letters he kept to hand out to women, he suffered greatly from his status as an ‘alien’ and all manner of highly improbable accusations were thrown at him. In ‘Dope Girls’ Marek Kohn says of him “His corruptive power over white women was accepted as fact, as was the presumption of his leading role in the drug traffic. Yet there is no evidence to support the belief that he supplied drugs, other than to his girlfriend.”

Freda Kempton was a girlfriend of Chang in one way or another. She died in 1922 with the cause given as suicide during a state of temporary insanity. A cocktail of unrequited love, a troubled childhood, the suicide of a friend and a weakness for cocaine, led her to write a note which began ‘Mother forgive me. The whole world was against me.’

As an habitué of nightclubs, Freda was well known to Mrs. Meyrick who said “I shall never forget Freda’s strained, white face as she made confession to me of her drug curse.” It was Chang’s unnerving influence over her ‘girls’ that made her eye him with intense suspicion and refuse him entry to her club. As an ‘alien’*, Chang would draw additional attention to Gerrard Street that would have been unwelcome but on the other hand it might have been useful for Mrs. Meyrick to have police scrutiny focused elsewhere.

The Raid

On the night of the 17th August police attention was firmly fixed on ‘The Palm Club’. With Davidson and Mepham having already gained entrance, Sergeant Goddard, PC Wilkin and Inspector Abiss would enter the premises at 12.20am.

Abiss report of the raid reads:

“Around the room were seven small and one large table, about 30 chairs, a settee and a piano. Just at the right of the entrance at a table, a man and a woman were seated. In front of the woman was a glass about half full of whisky. I told her she would be summoned for consuming intoxicants after permitted hours and she replied “Must you? That’s unfortunate.” This woman was nearly drunk. Whilst taking these particulars she snatched up the glass and consumed the contents.”

The woman gave her name to Inspector Abiss as Violet Siever of 84 Berwick Street.

In total, seven customers were found drinking on the premises after hours. These included Arthur Manse, who gave a hotel as his address, Briant Browton of Hyde Park, Joseph Cobbs who gave an address near Sandown Racecourse, George Ford with a Regents Park address and the aptly named Errol Hustler, with an address in Kensington.

When attention fell on Joseph Cobbs during the raid, he admitted he was drinking scotch, “It won’t be a hanging job will it?” he asked Inspector Abiss.

The only other woman to be charged that evening was Stella Irish, of Hunter Street. Possibly the argumentative woman that officers Mepham and Davidson had escorted home previously.

The Trial

The case was heard on September 28th 1923, at Bow Street. The summons against Manse was unable to be served and he appeared untraceable. Errol Hustler sent a note to say he was ill and in his absence he was fined £3, however he did not pay his fine and a warrant was issued but he was never traced. The other defendants pleaded guilty and were ordered to pay £3 each.

The manager, Claude Allen, was fined over £251 and was given 14 days to pay. The club was closed and struck off the register. During the proceedings no mention was ever made of Brilliant Chang however, his day of reckoning was to come the following year when he was found guilty of selling drugs to Violet Payne. The evidence was flimsy but he was jailed and subsequently deported nevertheless. Sergeant Goddard and PC Wilkin continued to rule the streets of Soho, presiding over a number of operations until their spectacular fall from grace in 1929.

In a letter dated October 1923, Commissioner of Police, William Horwood said of the Palm Club “It was an habitual resort, after permitted hours, of prostitutes and men of doubtful character whose re-appearance was nightly accompanied by disgusting scenes of drunkenness and disorder”. He urged the Secretary of State for legislation that would allow greater control of the clubs. The example of the Palm Club, he said, showed “the ease with which so-called clubs can commence and carry on business in defiance of the law.”

Far from stamping out vice, however, a year later no. 6 Gerrard St. made the police files again with accusations that it was now being run as a brothel. Today, it is a Grade II listed building and currently a Chinese restaurant, Feng Shui Inn.

* the use of the word ‘alien’ refers to the ‘Aliens Act 1905’. Whereby emigrants to England were registered and kept on a list.

Resources used in this article were Metropolitan Police documents at the National Archives, ‘Dope Girls’ by Marek Kohn, ‘Secrets of the 43’ by Kate Meyrick, ‘Sergeant Goddard: A Rotten Apple or Diseased Orchard?’ Clive Emsley, Ancestry and The British Newspaper Archive on Find My Past.

You might also enjoy this! https://www.sohobitespodcast.com/episode/10

If there are any corrections or suspected copyright issues, please do not hesitate to get in touch!

Leave a comment